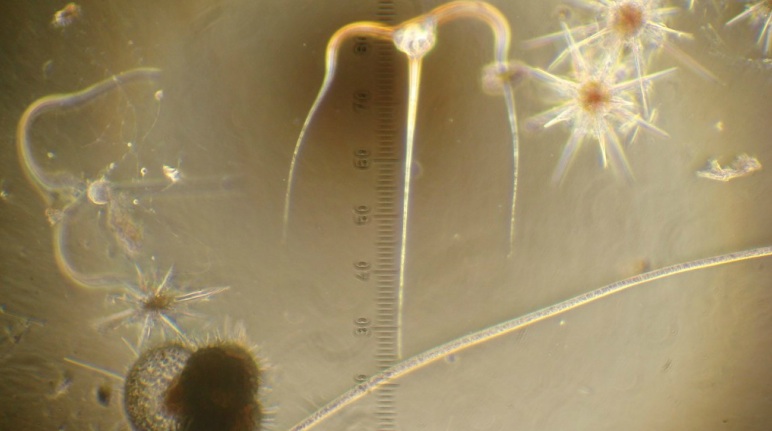

During a Pacific Ocean research cruise, Angel White peers into her microscope. The ship rides gentle swells and sways side to side. In her field of view, organisms the size of dust motes rise and fall through their own watery world. “It can be disorienting and enthralling at the same time. The microbes are dying as I look at them, and it doesn’t always make for the best photos,” she says.

White studies plankton, the microorganisms that power the marine food chain, pump oxygen into the atmosphere and regulate global chemical cycles. In the course of her research, she has recorded an astonishing diversity of living shapes, forms, colors and patterns: spiny Radiolarians, fat copepods, football-shaped ostracods and coiled threads of Trichodesmium that coalesce into filamentous balls. Under fluorescent light, her photos reveal organisms within organisms, glowing constellations that rival images from the best space telescopes.

White’s science is strictly down to Earth. The assistant professor in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences aims to reveal how plankton consume and release nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus and how, in turn, these abundant organisms respond to variations in temperature and water chemistry. Her tools run the gamut from high-tech instruments to old-school nets towed behind a ship. In the lab, her camera has become invaluable in her exploration of a world that is largely invisible to the naked eye.

“Photography is a wonderful outlet for creativity and discovery,” she adds. “Plankton show an amazing array of different adaptations to their environment. If you concentrate them in a drop of ocean water and look through the microscope, you will see organisms feeding, swimming, gliding, tumbling and floating. There are blues and reds, jaws and antennae — whole alien worlds.”

Call to Artists

In 2012, 35 Oregon artists took up a call from The Arts Center of Corvallis for works based on White’s plankton images. Submissions came from painters, fabric and glass artists, sculptors, potters and an expert in the ancient Japanese art of stencil dyeing. They comprised a show, The Art of Plankton, Form Follows Function.

The range of art gave White a new view of a world that she has explored through her research. “I’ve been fortunate over the years to look through a microscope and be thrilled with the familiar and the mysterious,” she says. “And now to have a whole range of creative people re-envision what I saw the first time is very cool. The natural world can be astonishingly beautiful.

“The general view is that scientists pick it apart and explain it through cold and methodical equations. It is easy to get lost in the details and lose a sense of wonder. This collaboration — merging the perspectives and talents of artists with science — is refreshing. It reminds me what it was like that first time at sea, the first time I realized that, ‘oh no, really, the ocean teems with life, glorious tiny life.’ That sense of discovery is what I felt talking to the artists.”

Drifters 1, Leah Wilson, Eugene

Drifters 1, Leah Wilson, Eugene

Leviathan, Rakar West, Eugene

Leviathan, Rakar West, Eugene

Parum Aqua Flora, Sidnee Snell, Corvallis

Parum Aqua Flora, Sidnee Snell, Corvallis

Emiliana Coccolithophore, Ella Rhoades, Corvallis

Emiliana Coccolithophore, Ella Rhoades, Corvallis

Drifters, Sara McCormick, Portland

Drifters, Sara McCormick, Portland

Blue Button, Sandra Schock-Houtman, Corvallis

Blue Button, Sandra Schock-Houtman, Corvallis

Tondos, Jenny Gray, Corvallis

Tondos, Jenny Gray, Corvallis

Benthos, Jerri Bartholomew, Corvallis

Benthos, Jerri Bartholomew, Corvallis

The Collection, Chi Meredith, Corvallis

The Collection, Chi Meredith, Corvallis

One reply on “Forms from the Sea”

The photography is not just constrained by the passion, but it is also useful in several ways. The photography is if a professional need than it is much an artistic trick. I really loved your article and these excellent art images.