You might have heard a few supposed facts about plastic in the ocean: 1) There is a massive swirling gyre of plastic, the “Great Pacific Garbage Patch,” between California and Japan that is twice the size of Texas; and 2) this plastic debris outweighs plankton and is growing in size. Interestingly, the scientific literature does not support these statements.

In 2008, I participated in one of the few scientific expeditions aimed at characterizing the abundance of plastic debris and the associated impacts of plastic on microbial communities. That expedition was part of research funded by the National Science Foundation through C-MORE, the Center for Microbial Oceanography: Research and Education.

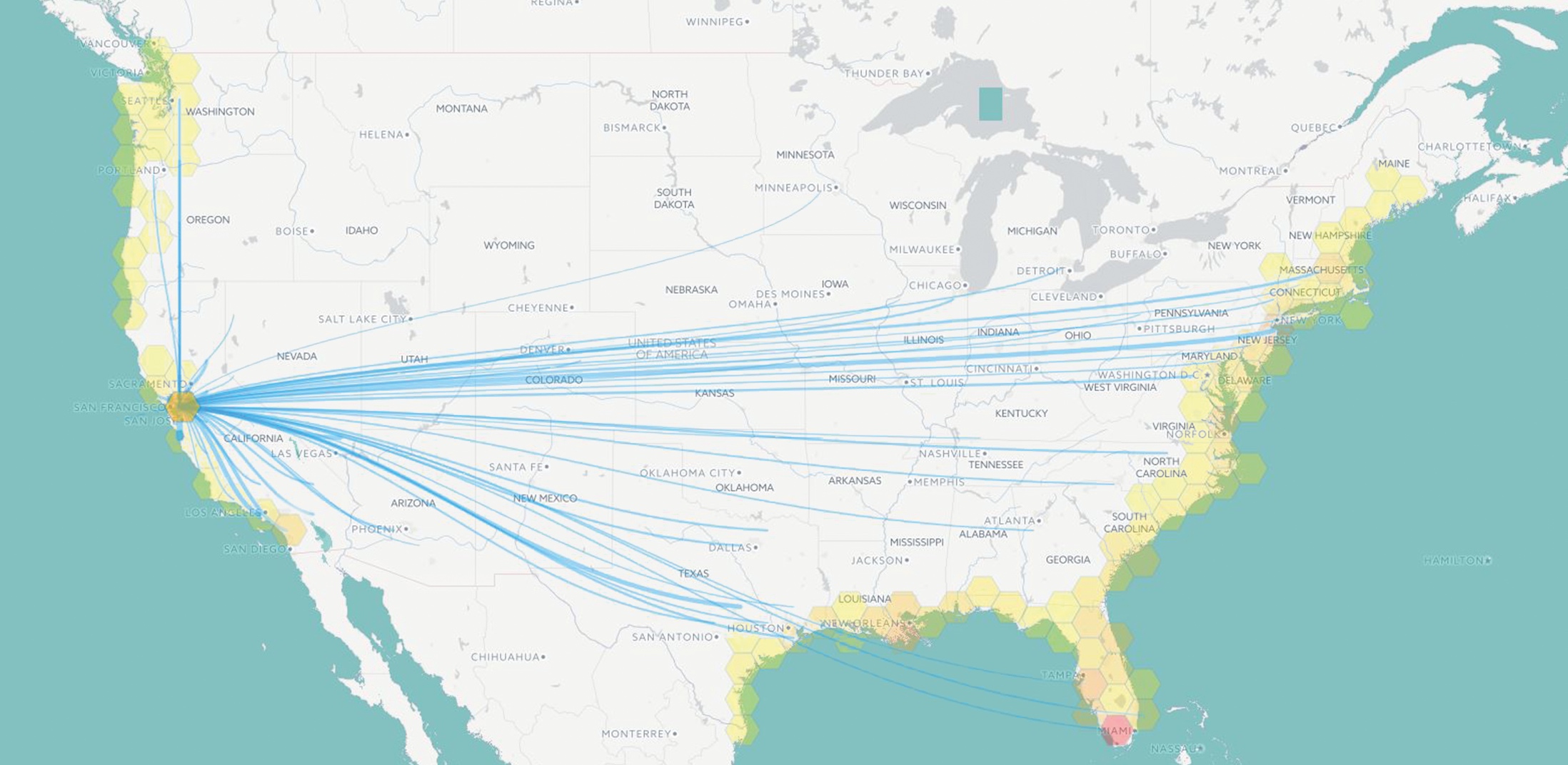

Standing on the bow of a research ship, floating in the heart of the alleged garbage patch, my colleagues and I looked out onto a calm, apparently pristine blue ocean. By towing a mesh net through these waters and deploying instruments capable of measuring particle size and abundance, it became clear that the sea around us actually contained few, very small pieces of plastic. If you were to line up 1,000 1-liter Nalgene™ bottles filled with ocean water from this location, one to five of them would contain a single piece of plastic roughly the size of a worn-down pencil eraser. In comparison, plankton (millions to billions of organisms per milliliter) outnumber and outweigh plastic by a considerable measure.

The amount of plastic out there isn’t inconsequential, but using the highest concentrations ever reported by scientists, the plastic debris floating in the surface waters of the North Pacific could be rounded up to produce a patch that is a small fraction of the state of Texas, not twice the size. This is not to say that the issue of plastic in the ocean should be dismissed; rather, the problem is more complex and enigmatic.

One of the longest records of ocean plastic comes from the western North Atlantic. Compiling a 22-year survey of plastic debris, researchers reported concentrations very similar to what we found in the Pacific, but there was a catch. The amount of plastic in the North Atlantic has not increased since the mid-1980s, despite a surge in plastic production over the same period. This unexpected conclusion has led to a lot of speculation: Are we doing a better job of preventing plastics from getting into the ocean? Is more plastic sinking out of the surface waters? Is plastic being more efficiently broken down? At present, we just don’t know.

New research findings may point to one part of the answer: microbes! Not only is plastic prime real estate for microbes, but they may actively degrade it. This interesting finding may partially explain the mystery of “missing plastic” in the Atlantic.

If there is a take-home message, it’s that plastic clearly does not belong in the ocean. The practical solution is to reduce the input of plastic into our oceans in the first place. There is no need to exaggerate the problem to Texas-sized proportions.

3 Comments

What are we, as consumers of information, to do when we encounter disparate findings from sources of seemingly equivalent credibility? The issue of plastic in our oceans greatly concerns me, but I often find myself wondering which scientist to believe. And this problem of varied and conflicting information prevails across all environmental issues.

http://marine-litter.gpa.unep.org/documents/World's_largest_landfill.pdf

http://www.algalita.org/AlgalitaFAQs.htm

The information linked above isn’t in total conflict, but it certainly implies a level of gravity not reached in your research.

I think your confusion on this issue is understandable, but “sources of seemingly equivalent credibility”? Captain Charles Moore? A credible scientific source? I’m sorry, but he doesn’t have the research or professional background to be “equivalent” to Dr. White on this issue. Yes, he has been out to the central Pacific gyre a few times. Yes, he has published papers. However, he isn’t a trained scientist and his level of advocacy on this issue puts him in ethical conflict with his ability to speak impartially about the data. After you wade through the media hoopla and get to the real scientific literature, the actual data show that the concentrations of plastic are quite small. Dr. White’s analogy with the 1-liter water bottles is accurate.

I agree with the take-home message here: plastic does NOT belong in the ocean. But as a scientist myself, I think it’s important to recognize that we don’t have to exaggerate the issue in order to advocate for change.

I certainly agree that plastic does not belong in the oceans, but it is good to hear that some of the startling statistics have been somewhat exaggerated. The fact that microbes seem to be “eating” the Atlantic’s plastic also seems like good news to me. Anything that can be done, by people or nature itself, to reduce pollutants in the ocean is a good thing.