From high in the air, the view looked devastating: Dead trees stretched to the horizon. Much of the wilderness landscape was covered in what forest scientists dispassionately call the “gray phase.” The term aptly captures what’s left after needles and cones fall to the ground — a sea of decaying sticks, dotted with islands of green.

In 2016, such a scene greeted Anna Talucci, an Oregon State University Ph.D. student who was in a small plane scanning the landscape in the heart of British Columbia. She was on her way to take a closer look on the ground.

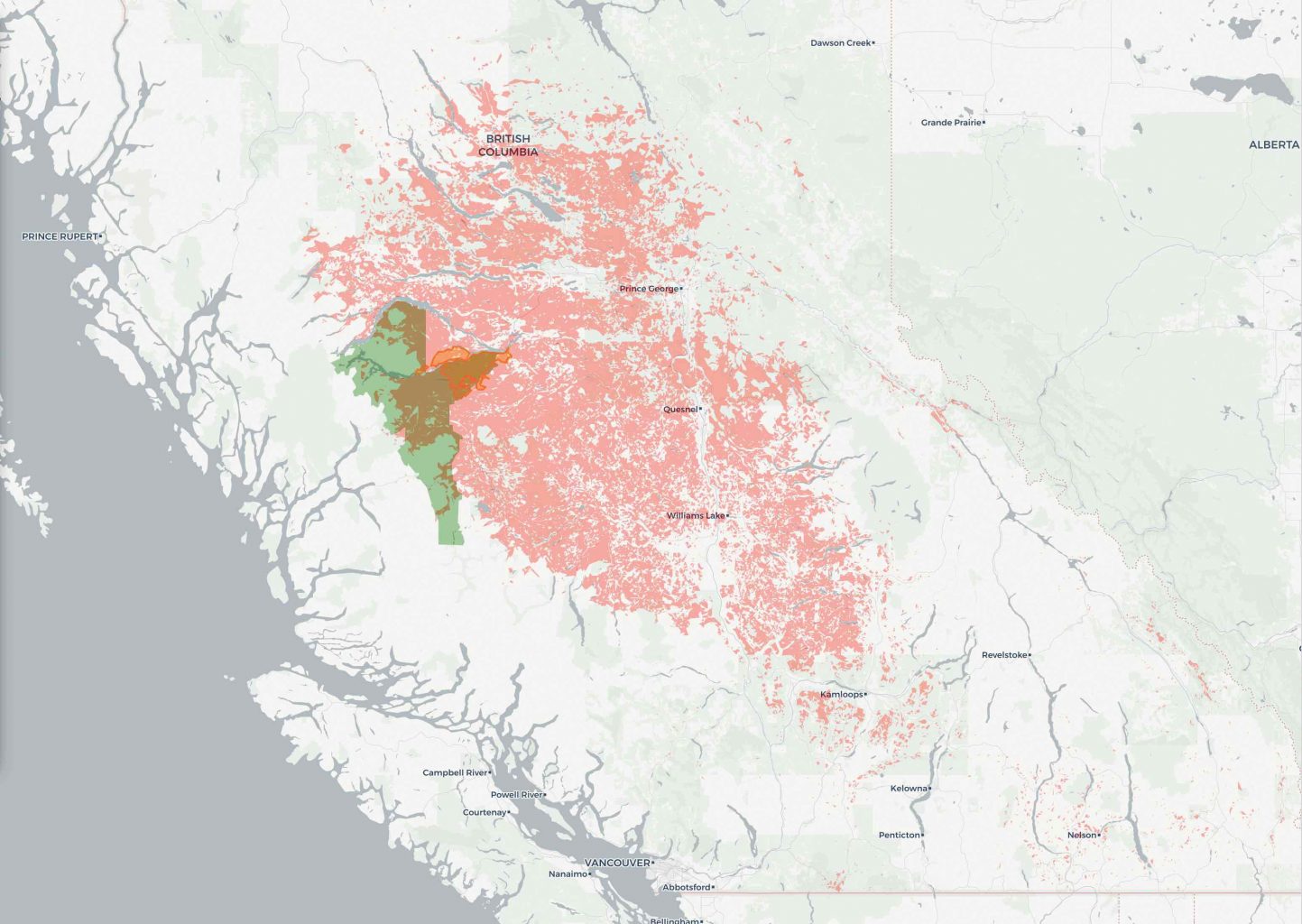

Starting in the mid 1990s, mountain pine beetles killed lodgepole pines across the province in a huge swath totaling 18 million hectares (44.4 million acres), an area the size of Washington state. In their wake between 2012 and 2014, three lightning-caused wildfires burned through some of the beetle-killed forest.

Because the fires occurred in parks managed as wilderness, where there was no effort to surround the flames, the sequence of insect outbreak followed by fire gave scientists like Talucci a chance to look at the natural resilience of these forests. Did the fires burn more severely where forest stands were dominated by dead trees? And what was the combined impact of beetles and fire on forest regeneration?

The Pennsylvania native and graduate student in the College of Forestry took a two-pronged approach. She tramped into the wilderness, setting up 63 fire-burned plots and measuring fire severity, regeneration and structure, the charred remains of burned stands.

With guidance from her advisor, Assistant Professor Meg Krawchuk, she also took a wider view through satellite imagery that showed changes across the landscape. She analyzed regeneration trends and factors that could explain where fires burned more or less intensely.

“I have an affinity for wilderness areas, and this is probably the most remote wilderness setting I have been,” says Talucci, who has spent time in the Rockies of Wyoming as an employee of the National Outdoor Leadership School.

Last spring, in a paper published in the journal Ecosphere, Talucci reported finding little to no correlation between fire severity and beetle-killed trees. Other factors, such as wind speed, humidity and temperature, exert a stronger influence on fire behavior. However, she did show that gray-phase trees, aka snags, burned differently than those that were alive at the time of the fire. Long-dead trees tend to smolder longer. The deeply charred remains could influence the kind of habitats favored by insects and birds that flock to burned forests.

Nevertheless, lodgepole pine forests depend on fire to open their cones and allow seeds to sprout. “Enough of a seedbank exists to support regeneration that exceeds pre-disturbance stand densities, even with the 10-year lag between beetle outbreaks and wildfire,” Talucci says. That finding was published in the journal Forest Ecology and Management.

“Anna’s work was an impressive lift, blending field-based and computing-intensive fire ecology with application to forest management, carbon science and biodiversity conservation,” says Krawchuk. “She revealed important and largely unrecognized signatures of overlapping disturbances in forests.”

Talucci received her degree last spring and now works as a post-doctoral scientist at Colgate University in New York state. As a post-doc, Talucci is studying the fire ecology of Siberian larch forests.

“Dead Forests Burning”

See what Talucci saw from the air and on the ground in her online storymap, “Dead Forests Burning.” Talucci created the illustrated journey to show viewers where these landscape-altering events are taking place and bring her data down to Earth.

On her way to earning a certificate in geographic information systems, Talucci created the presentation in a geovisualization class taught by Bo Zhao, an OSU assistant professor of geography. Michael Cook, an undergraduate in natural resources, collaborated on the project.