All Scott Sell wanted to do was to prove Richard Mikula wrong. “He was one of those teachers who makes you want to learn. He was tough,” says the Oregon State University senior from Ashland, Oregon.

In his drive to show a thing or two to his former high school chemistry teacher, Scott has become a key player in a long-term environmental research project at one of the nation’s premier ecological research sites, the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest in the Oregon Cascades.

In high school, the avid camper and rock climber preferred searching for toeholds on a vertical rock face to cracking the books. He got C’s in Mikula’s class but did well — scoring a 4 on a scale of 1 to 5 — on the Advanced Placement chemistry test. Scott heard from a friend that Mikula was surprised.

At OSU, Scott traded his climbing ropes for lab notebooks. He majored in advanced chemistry, running experiments and analyzing results. He lasted about a year and a half. After an instructor told him that his academic program wouldn’t ever allow for much outdoor exploration, he switched to environmental chemistry.

Scott comes from an active and competitive family (younger brother Tyler is a nationally ranked rower) and was looking for opportunities to combine chemistry with environmental issues. In an internship search, he just happened to walk into Kate Lajtha’s office in the Department of Botany and Plant Pathology.

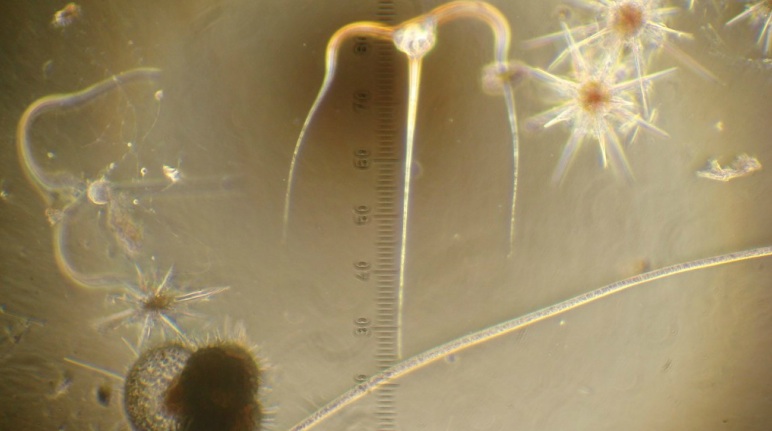

Lajtha, a botanist who focuses on soils and vegetation, leads a project with a name that is true to her calling: DIRT (Detrital Input and Removal Treatments). The real dirt is where much of the action happens in a forest. Carbon, nitrogen and other chemicals cycle through forest soils, she says, in a dynamic process that she calls “a nightmare of variability.” DIRT focuses on what controls those cycles and particularly how disturbance — tree harvesting and plant growth — affect the stability of carbon in the soil. The results could apply to efforts to sequester more carbon in forest soils across the world.

Through Lajtha’s lab, Scott learned how to analyze soil samples for major elements and micronutrients. He maintained databases, developed statistics and assisted graduate students. He learned, in short, to take ownership of the scientific process. He will become a co-author on scientific papers, an achievement that will help pave his way to graduate school.

Last summer, Scott completed his senior year working as a research assistant at the Andrews Forest. He managed a sophisticated new device (cavity ring-down laser spectrometer) that automatically analyzes air samples for isotopes of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. Last winter, when it stopped working, Scott contacted the manufacturer, made repairs and conducted weekly tests.

“The work is self-directed,” he says. “I love that I get out to the Andrews. I get to spend all this time out in forest. It’s beautiful and serene and quiet.”

Scott hopes to apply his knowledge by teaching chemistry or working for a company or government agency cleaning up pollution at oil spill and Superfund sites. That, he says, would indeed make Richard Mikula proud.